Feature Shoot |

|

Posted: 13 Aug 2015 05:00 AM PDT

Tunda   It is with a self-aware sort of swollen nostalgia, colored by childhood, memory, and the distinctive confines of a particular historical moment that photographer Michal Solarski recalls the annual holiday trek made with his family in the early ‘80s from Soviet-controlled Poland to the Hungarian Lake Balaton—or theHungarian Sea, as it is still often called by the land-locked Hungarians who vacation there. Like Dorothy whisked away from dreary, storm-struck Kansas to the magnificent Land of Oz, Solarski arrived at Lake Balaton as one temporarily but rapturously suspended from reality. Over the course of the 300-mile car trip, the cold monochrome scenery seemed to gradually dissolve into a vivid Technicolor dreamscape abounding with sights, sounds, and smells, all drunk in ravenously upon arrival through senses starved by daily life in the occupied East Bloc. Travel opportunities were limited for those living on the eastern side of the Iron Curtain, and a permit was required to travel across the border into Hungary. As most other holiday destinations were off limits, Lake Balaton formed a convenient meeting point for local Hungarian workers and those families from Eastern Bloc countries lucky enough to receive a permit in exchange for having demonstrated a sufficiently hardworking, non-rebellious attitude. For many, the place represented a rare and precious reprieve, and children were far from the only ones to revel in its relative charms. Returning many years later, Solarski strove to not only to compensate for a wholly undocumented time in his life – save for one image – but also to find whether a lake could still become a sea in the mind’s eye of one who now had seen the ocean. “When one wishes to recollect,” wrote Aristotle in On Memory and Reminiscence, “this is what he will do: he will try to obtain a beginning of movement whose sequel shall be the movement which he desires to reawaken.” Foregoing a sense of strict intentionality, Solarski drifted around the resort, feeling for intangible triggers that would spur the creation of an image encapsulating some quality of his time there. Counter-intuitively, staging became, at times, a form of achieving a personal sense of authenticity. Is it possible to recreate a mode of seeing no longer innate? In his imaginary photo album, The Hungarian Sea, Solarski seeks to answer this.   Basket and Goals. Club Aliga used to be a summer resort centre, exclusive to high-ranked Hungarian communistic party members as well as Fidel Castro, Mao Zedong and Yuri Gagarin, among others. Now the center is open to the public.  Ester, Zolan and Beri You say upon returning as an adult, you no longer found Balaton to be the paradise you once did. What exactly were your first impressions of it upon returning? Did the disconnect between your past and present visions of Balaton strike you as problematic or as something that could be reconciled through the photographic medium? “I had no idea what to expect to see there. Before going there to do the project, a friend of mine told me that whilst in Budapest, he saw an advert on TV depicting Balaton as some kind of a new ‘Acapulco’ in Central Europe, filled with a young crowd that flooded Balaton every weekend to party. This wasn’t something that I hoped to see. And indeed, it wasn’t. Upon arrival, my first impression was that Balaton had hardly changed, the vibe was still the same. There were similar people and a similar atmosphere to what I remembered from years ago. “It did not appear to me as paradise though. Apart from for the obvious reasons, like the twenty something year gap, all the life experiences I have had as an adult, and going there to do the photographic project, there was also something else. When I was spending holidays there with my family twenty-odd years ago, I was part of a vacationing crowd. We were all there for the same reason – to enjoy summer in a beautiful place and to spend quality time with the close ones. This time it was different, I was a kind of voyeur looking at others from a distance. I felt excluded, strange, and very lonely at times. As a child I wanted the summer at the lake to last forever, this time I was looking forward to going back home.”  Austrian Twins Were you systematic in your approach to photographing this series? In other words, did you have particular individual images and moments in mind that you were determined to capture or recreate, or did you approach the project more intuitively, with the aim to create a body of work that captured the general feeling you recalled? “I did not have anything structured in mind – no particular scenes or situations. I just wanted to capture the atmosphere and feeling of what I remembered. The places, colours, and the kind of people I reminisced from years ago. I wanted to imagine being myself as a little boy, and to capture what I saw around me on film. I spent days just wandering around from dawn till dusk looking at people, and if there was something about the way they looked, or the situation they were in, which triggered my emotions, I approached them and asked them to pose in front the camera.”  In your latest series, Cut it Short, you also return to an important site of your childhood with the aim to photographically recreate your childhood vision of a specific place and time. Would you describe yourself as someone spurred on by nostalgia or are there other more complex qualities of memory you are particularly interested in exploring? “As I consider my childhood to be a very happy period of my life, my work is, to some extent, driven by nostalgia, but I am also interested in how the reality is altered by our projection of memory. Our minds can play tricks on us by changing illusions of what we think we hear and see, into what seems like reality. My recent work is a balancing act between both documentary and fictional narrative. The border between the two is fluid. This is where I see myself as an artist.” “Cut It Short approaches the subject of memory from a completely different perspective – using staged photography to recreate past events. It is a new area which I am exploring within my artistic practice and I find it immensely intriguing.”  Husky Dog  Were you satisfied with the series’ ability to retroactively document this undocumented time in your life, to capture this quality of memory you sought? Or did you find, rather, that it became something else altogether? “I think it became something else. It’s neither a record of my childhood holidays nor the evidence of the present. These contemporary images simply cannot be a documentation of summer vacations that happened thirty years ago. They also aren’t showing the place as it is now as I intentionally distorted the reality in order to achieve something that is supposed to be a projection of my memory. I am satisfied in that sense. When I look at my images I see the place as I remember it.”   Ester and Adam Is there any one particular image or two that feel most representative to you? “If I have to think of the most representative images, one of them would be the portrait of Ester and Adam (siblings holding hands on the waterfront). This image somehow reminds me of the only remaining image I have from my family holidays in Balaton. It’s a blurry picture of my sister and I, that was taken somewhere on one of the lake’s piers. This snapshot is the only reminiscence of six subsequent summers spent by the lake and so it has become very important to me. When I took this image, I was thinking of the photograph of my sister and I and so it resonated deeply to me. “The other one could be a picture of Botond and Doly (the boy with his dog standing on the stage of the open air theatre). For me it’s almost metaphorical – this little boy looks so vulnerable in comparison to both his dog and the surroundings. It’s almost the same as I felt coming to that strange new world.”  Botond and Doly     All images © Michal Solarski The post Greetings From The Hungarian Sea appeared first on Feature Shoot. |

|

Posted: 12 Aug 2015 09:54 AM PDT

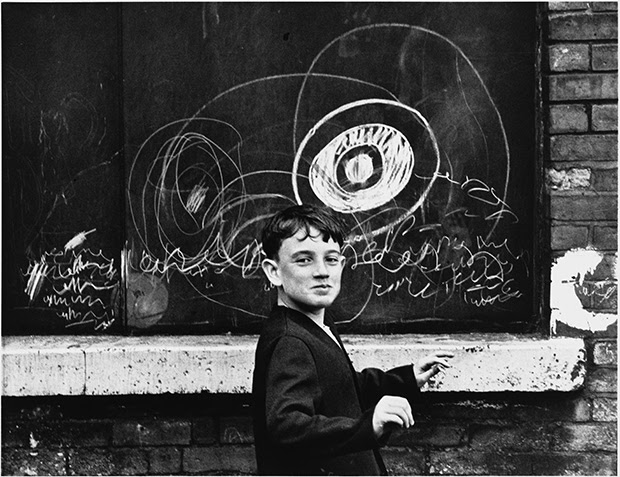

Manchester, 1968, © Shirley Baker Estate, Courtesy of Mary Evans Picture Library  Hulme, July 1965, © Shirley Baker Estate, Courtesy of the Shirley Baker Estate  Manchester, 1967, © Shirley Baker Estate, Courtesy of the Shirley Baker Estate The streets of the Manchester slums, in which children played on concrete roads and their parents watched as terraced homes were razed to the ground in favor of new developments, became in the 1960s and two decades following like a home away from home for British street photographer Shirley Baker (1932-2014), whose middle class family owned a furniture store in Salford. Baker, reports curator Anna Douglas, whose exhibition Shirley Baker: Women, Children and Loitering Men is now on view at The Photographers’ Gallery in London, is recognized as the sole female photojournalist working in the streets of Britain during the post-war decades. Inner city Manchester and Salford became her constant subject in the mid-20th century, when she witnessed the beginnings of the demolitions that would sweep the area, forcing large families from their already small living quarters and into illegal squats. Cranes leveled the blocks, and houses were evacuated and left vulnerable to break-ins and vandalisms by neighborhood kids. These streets and their homes, erected to house the working class families that sent their mothers and fathers to labor in nearby factories, had by the time Baker began photographing them, surrendered to industrial grime. Bricks were painted in a layer of soot, and drinking water was no longer clean. There was little space to make a home, and none for children to play, and yet youngsters spilled out into the streets in groups to congregate and frolic about with their toys. It was the children who most loved Baker; when she arrived, camera in hand, they circled her and pleaded that she take their picture. The scenes captured in Baker’s gaze no longer persist; the apartments that replaced them, in fact, have also been substituted with newer housing. For Douglas, however, these images escape relegation to the realm of wistfulness or sentimentality; instead, they reach through the decades to touch on themes and characters that carry weight and meaning today. Yes, they are documentary images, but for Douglas, they can also be symbolic ones, those that speak to an abiding vigor and resilience of the human spirit. Shirley Baker: Women, Children and Loitering Men is on view until September 20th, 2015.  Hulme, 1965, © Shirley Baker Estate, Courtesy of Mary Evans Picture Library  Hulme, July 1965, © Shirley Baker Estate, Courtesy of the Shirley Baker Estate  Hulme, May 1965, © Shirley Baker Estate, Courtesy of the Shirley Baker Estate  Manchester, 1964, © Shirley Baker Estate, Courtesy of Mary Evans Picture Library  Near Upper Brook St, Manchester, 1964 © Shirley Baker Estate, Courtesy of Mary Evans Picture Library All images © Shirley Baker via The Guardian The post ‘Women, Children and Loitering Men': A Glimpse at Manchester’s Slums in the 1960s appeared first on Feature Shoot. |