Kislev 22, 5771 · November 29, 2010

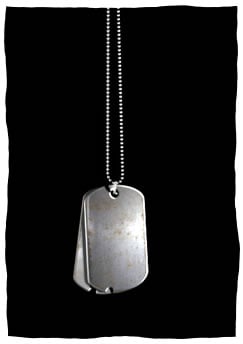

The Dog Tag Dilemma

Do you know what a Protestant B is? I know what a Protestant is,

and I know what a Catholic is, and I know what a Jew is . . . but until

recently, I had never heard of a Protestant B.

I learned what a Protestant B is from an essay by Debra Darvick

that appeared in an issue of Hadassah Magazine. It is a chapter from a

book she is working on about the American Jewish experience. And this

essay is about the experience of retired Army Major Mike Neulander, who

now lives in Newport News, Virginia, and who is now a Judaic

silversmith. This is his story.

Dog tags. When you get right down to it, the military's dog tag classification forced me to reclaim my Judaism.

In the fall of 1990, things were heating up in Kuwait and Saudi

Arabia. I had been an Army captain and a helicopter maintenance test

pilot for a decade, and received notice that I would be transferred to

the First Cavalry Division, which was on alert for the Persian Gulf War.

Consequently, I also got wind of the Department of Defense "dog tag

dilemma" vis-�-vis Jewish personnel. Then as now, Jews were forbidden by

Saudi law to enter the country. But our Secretary of Defense flat-out

told the king of Saudi Arabia, "We have Jews in our military. They've

trained with their units and they're going. Blink and look the other

way."

Then, as now, Jews were forbidden by Saudi law to enter the country

With Kuwait occupied and the Iraqis at his border, King Fahd did the

practical thing. We shipped out, but there was still the issue of

classification. Normally the dog tags of Jewish servicemen are imprinted

with the word "Jewish." But Defense, fearing that this would put Jewish

soldiers at further risk should they be captured on Iraqi soil,

substituted the classification "Protestant B" on the tags. I didn't like

the whole idea of classifying Jews as Protestant-anything, and so I

decided to leave my dog tag alone. I figured if I were captured, it was

in G‑d's hands. Changing my tags was tantamount to denying my religion,

and I couldn't swallow that.

In September 1990 I went off to defend a country that I was

prohibited from entering. The "Jewish" on my dog tag remained as clear

and unmistakable as the American star on the hood of every Army truck.

A few days after my arrival, the Baptist chaplain approached me. "I

just got a secret message through channels," he said. "There's going to

be a Jewish gathering. A holiday? Simkatoro or something like that. You

want to go? It's at 1800 hours at Dhahran Airbase."

Simkatoro turned out to be Simchat Torah, a holiday that hadn't

registered on my religious radar in eons. Services were held in absolute

secrecy in a windowless room in a cinder block building. The chaplain

led a swift and simple service. We couldn't risk singing or dancing, but

Rabbi Ben Romer had managed to smuggle in a bottle of Manischewitz.

Normally I can't stand the stuff, but that night, the wine tasted of

Shabbat and family and Seders of long ago. My soul was warmed by the

forbidden alcohol and by the memories swirling around me and my fellow

soldiers. We were strangers to one another in a land stranger than any

of us had ever experienced, but for that brief hour, we were home.

The wind was blowing dry across the tent, but inside there was an incredible feeling of celebrationOnly

Americans would have had the chutzpah to celebrate Simchat Torah under

the noses of the Saudis. Irony and pride twisted together inside me like

barbed wire. Celebrating my Judaism that evening made me even prouder

to be an American, thankful once more for the freedoms we have. I had

only been in Saudi Arabia a week, but I already had a keen understanding

of how restrictive its society was.

Soon after, things began coming to a head. The next time I was able

to do anything remotely Jewish was Chanukah. Maybe it was coincidence,

or maybe it was G‑d's hand that placed a Jewish colonel in charge of our

unit. Colonel Lawrence Schneider relayed messages of Jewish gatherings

to us immediately. Had a non-Jew been in that position, the information

would likely have taken a back seat to a more pressing issue. Like war.

But it didn't.

When notice of the Chanukah party was decoded, we knew about it at

once. The first thing we saw when we entered the tent was food, tons of

it. Care packages from the States-cookies, latkes, sour cream and

applesauce, and cans and cans of gefilte fish. The wind was blowing dry

across the tent, but inside there was an incredible feeling of

celebration. As Rabbi Romer talked about the theme of Chanukah and the

ragtag bunch of Maccabee soldiers fighting Jewry's oppressors thousands

of years ago, it wasn't hard to make the connection to what lay ahead of

us. There, in the middle of the desert, inside an olive green tent, we

felt like we were the Maccabees. If we had to go down, we were going to

go down fighting, as they did.

We blessed the candles, acknowledging the King of the Universe who

commanded us to kindle the Chanukah lights. We said the second prayer,

praising G‑d for the miracles He performed, in those days and now. And

we sang the third blessing, the Shehecheyanu, thanking G‑d for keeping us in life and for enabling us to reach this season.

We knew war was imminent. All week we had received reports of mass

destruction, projections of the chemical weapons that were likely to be

unleashed. Intelligence estimates put the first rounds of casualties at

12,500 soldiers. I heard those numbers and thought, "That's my whole

division!" I sat back in my chair, my gefilte fish cans at my feet. They

were in the desert, about to go to war, singing songs of praise to G‑d

who had saved our ancestors in battle once before.

The feeling of unity was as pervasive as our apprehension, as real as

the sand that found its way into everything from our socks to our

toothbrushes. I felt more Jewish there on that lonely Saudi plain, our

tanks and guns at the ready, than I had ever felt back home in

synagogue.

That Chanukah in the desert solidified for me the urge to reconnect

with my Judaism. I felt religion welling up inside me. Any soldier will

tell you that there are no atheists in foxholes, and I know that part of

my feelings were tied to the looming war and my desire to get with G‑d

before the unknown descended in the clouds of battle. It sounds corny,

but as we downed the latkes and cookies and wiped the last of the

applesauce from our plates, everyone grew quiet, keenly aware of the

link with history, thinking of what we were about to do and what had

been done by soldiers like us so long ago.

Silently, he withdrew the metal rectangle and its beaded chain from beneath his shirt

The trooper beside me stared ahead at nothing in particular,

absentmindedly fingering his dog tag. "How'd you classify?" I asked,

nodding to my tag. Silently, he withdrew the metal rectangle and its

beaded chain from beneath his shirt and held it out for me to read. Like

mine, his read, "Jewish."

Somewhere in a military depot someplace, I am sure that there must be

boxes and boxes of dog tags, still in their wrappers, all marked

"Protestant B."

By Doron Kornbluth

More articles... |

Doron Kornbluth is the author of Raising Kids to LOVE Being Jewish

and a popular international lecturer. His popular free "Keeping our

families Jewish" e-newsletter helps thousands of families keep our

identity strong. To join the list, or visit Doron, visit his website. |

|